As the uranium bull market is in full swing, I thought it's time to take a look at status of uranium in Sweden

Uranium in Sweden

With the Swedish government increasingly highlighting the importance of nuclear energy and a proposed lifting of the current uranium mining ban just around the corner, I thought it was time to delve a bit deeper into this topic from a geologist’s perspective and have a more detailed look at the status of the uranium industry in Sweden.

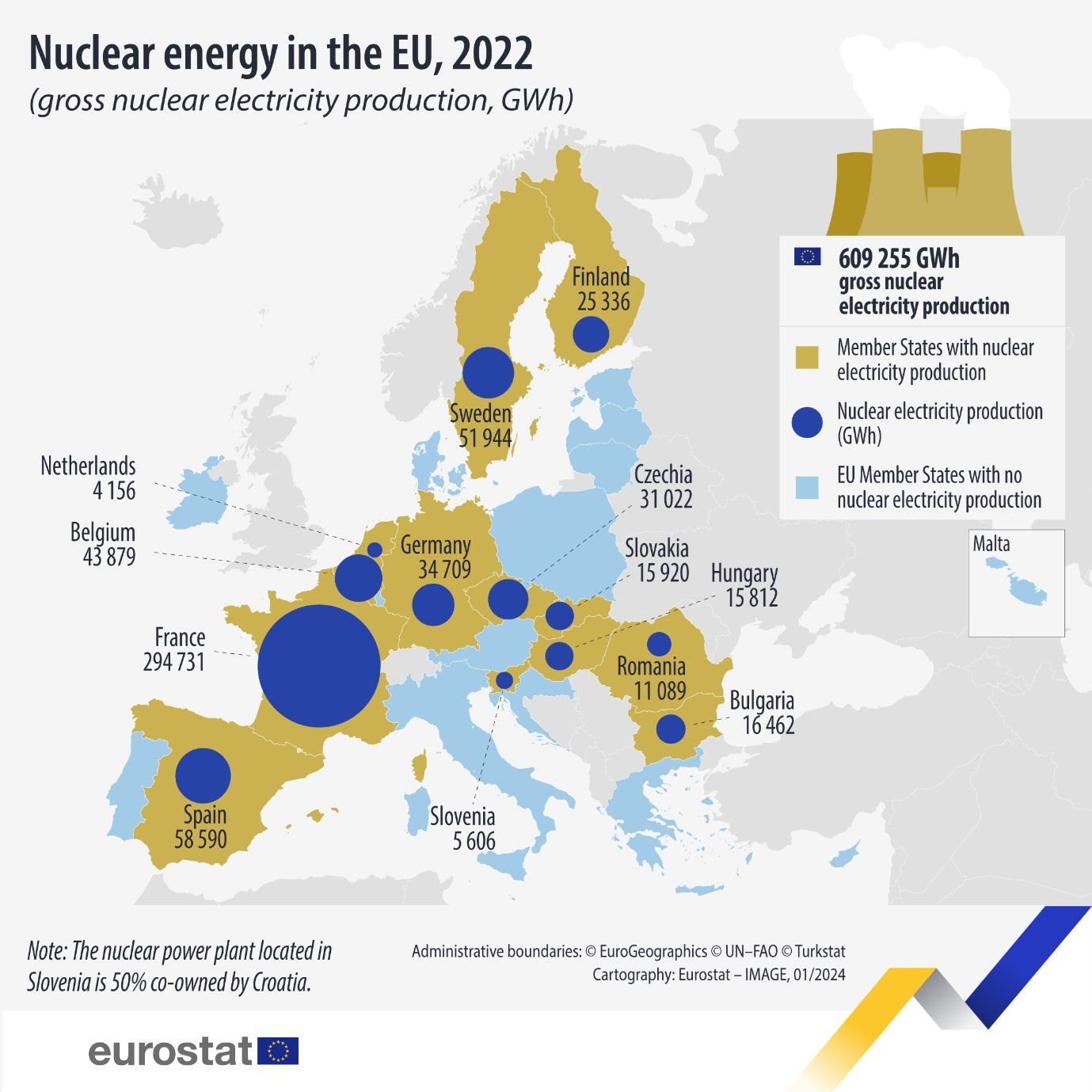

Unbeknownst to many, Sweden is one of Europe’s top producers of nuclear power, with currently six active reactors producing somewhere between 30-40% of the country’s electricity (50,000 GWh or 50 TWh). To fuel these reactors, approximately 1,500t of U3O8 are needed each year. In comparison, Europe’s yearly consumption currently stands at 12,500t, while the whole world needs around 65,000t per annum. Sweden itself has no domestic enrichment capacities but hosts a large Westinghouse facility in Västerås that supplies around 30 European reactors with final nuclear fuel cells.

The amount of uranium needed in Swedish reactors is set to increase significantly to somewhere between 3000t and 4000t per annum, as the country strives to electrify its society to reach its 2045 net-zero carbon emission goal. As part of this electrification process, the country needs to approximately double its electricity output to around 300 TWh over the next 20 years, with nuclear power envisaged to continuously play an important role. Interestingly, the increased demand for electricity appears to be in large part related to the decarbonization plans of the Swedish iron and steel industries through hydrogen reduction and electric arc furnaces.

Recognizing the challenge of increasing electricity output without expanding nuclear power capacity, the government was forced to act sooner or later. Over the last few years, this has resulted in multiple legislative changes, initiated by a reframing of the country’s energy goals from 100% renewable to 100% fossil-free, thereby including nuclear power.

In short, the government now plans to add two more conventional reactors by 2035 and the equivalent of 10 conventional reactors by 2045, potentially adding small modular reactors to the mix.

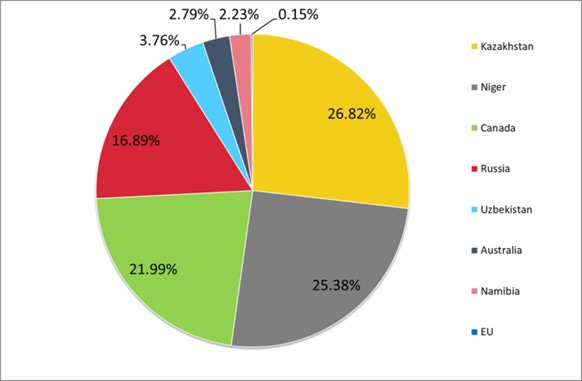

When it comes to the question of sourcing its uranium, it is important to note that Sweden is part of Euratom, a European organization coordinating the supply of uranium for its members to ensure a certain degree of supply chain diversification.

While previously relatively stable, the aftermath of the Russian invasion of Ukraine and recent political developments in West Africa, now threaten a significant share of Euratom’s supply lines. Although replacing those capacities with other oversea providers remains a possibility, it is obvious that a shift to domestic production becomes ever more favorable.

Uranium Mining In Sweden: Great Potential

So how could Sweden contribute to securing Europe’s and thereby its own electricity supply? Fortunately, or unfortunately, depending on your viewpoint, some of the world’s largest uranium resources are hidden in Sweden’s bedrock and could, in theory, supply the whole of Europe with all its needs for decades or even centuries to come.

Historically, the different uranium deposits and occurrences in Sweden have been divided into shale and “hard rock” type deposits, of which the latter category includes some of the classical uranium mineralization styles like roll front type deposits or mineralization related to granitic intrusions. However, from what we know so far, these occurrences are relatively limited in size. That said, some of the known occurrences could be expanded in the future and more exploration for conventional uranium deposits is warranted, not least as a more than1000km long unconformity is dissecting large parts of the country.

Whereas the “hard rock” deposits are generally viewed as moderate to high-grade (0.05%-0.1% U3O8) deposits, the shale-hosted mineralization, or more precisely the mineralization in the Alum shale formation, has an average grade of approximately an order of magnitude lower, usually containing around 0.005%–0.03% U3O8. These deposits have historically been referred to as “unconventional deposits”, a terminology that might soon be outdated. While having relatively low grades, these deposits are laterally very extensive and thus can hold a significant amount of uranium as we soon shall learn. The map below visualizes the worldwide distribution of uranium contained in unconventional deposits.

Alum Shales

The Alum shales are a laterally extensive formation of bituminous shales covering large parts of Sweden, and, to a lesser extent also Norway. They are of Cambrian to lower Ordovician age and have been thrust several hundred kilometers towards the east during the closure of the Iapetus Ocean in mid-Palaeozoic times, now forming an allochthone, unconformably overlying the Svecofennian basement rocks. The thrusting has important implications for potential mining scenarios, as it stacks the shales that are usually only several meters to 10’s of meters thick to locally more than 200m thick packages, greatly increasing the tonnage of these deposits.

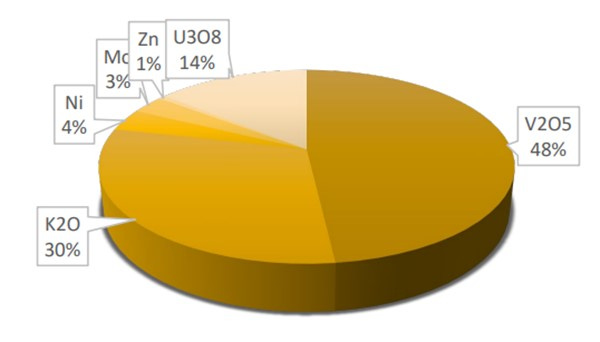

Although the shales are currently in the spotlight due to the uranium debate, their value is by no means limited to this commodity. Indeed, as for example in the case of the Häggån deposit, most of the value lies in vanadium and potash, with uranium being only a high-value by-product. Locally, the shales also contain elevated grades of rare earth elements, that could, if recoverable, become a valuable asset in itself.

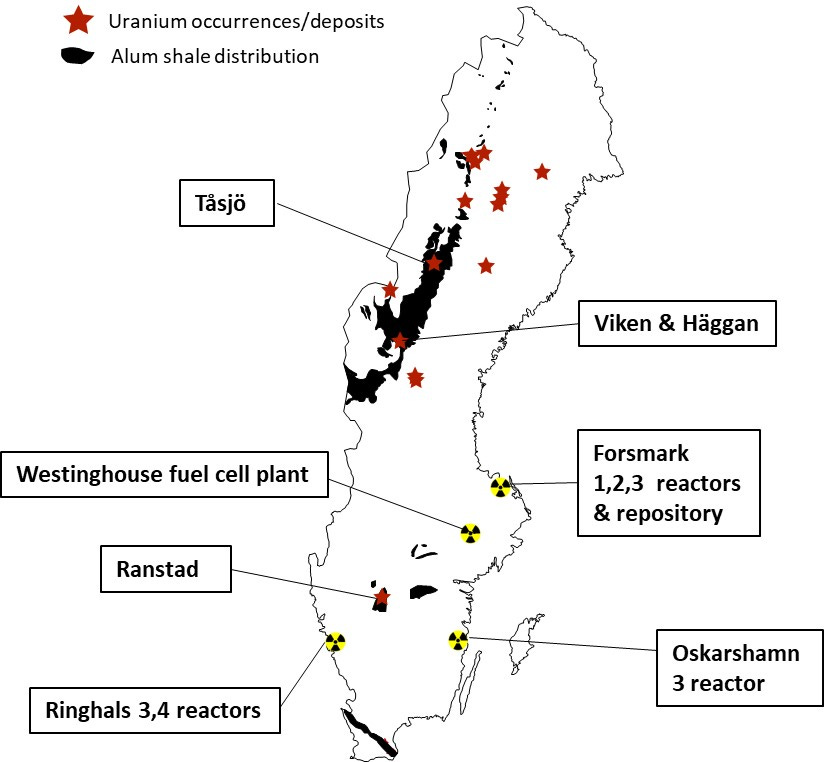

While not necessarily the primary economic metal, the amount of uranium occurring in these deposits is, however, significant. With hundreds of thousands to millions of tons of contained uranium, the three largest currently known Alum shale deposits (Ranstad: 1 722 000t U3O8, Viken/Häggån: 756 189t U3O8, Tåsjö: 40 000t U3O8) compete with the world’s largest known accumulation of uranium – the supergiant Olympic Dam deposit in southern Australia that currently boasts resources of more than 2 000 000 million tons contained U3O8.

Currently, the main actors actively positioning themselves for the anticipated lifting of the moratorium on uranium mining and exploration are District Metals (TSXV:DMX), Aura Energy (ASX:AEE) and Mawson Gold (TSXV:MAW), of which the latter two have already been active in Sweden during the 2007 bull market. District Metals is a newcomer to the Swedish uranium market but brings with it experience from the Canadian uranium industry and has several years of operating experience in Sweden, exploring for other metals. Of those three companies, only Mawson Gold is focusing on the hard rock occurrences, while the other two are generally eying the potential upside the Alum shales have to offer.

District Metals has recently consolidated 100% of the Viken deposit and holds, among other, claims over the Tåsjo area, whereas Aura Energy is currently advancing the Häggån deposit, primarily as a vanadium-potash dominated polymetallic project. As Aura has been active in Sweden since the last uranium bull market, the company needs to file a mining lease application this year to keep its rights on the deposit. In preparation thereof, Aura recently published a scoping study that outlines a scaled-back mining scenario in a small part of its license area. Under this scenario, uranium will not be recovered, but instead stabilized in a calcium-phosphate matrix for disposal in the tailings. If the moratorium were to be lifted, and if the Swedish government and local community wish to do so, an additional circuit allowing for the extraction of uranium could be added.

The moratorium came initially into effect on August 1, 2018, essentially removing uranium as a concession mineral and thereby forbidding any recovery and sale of the energy metal. Shortly after the new government was elected in 2022, a motion was put in place to lift the moratorium and change the mining code back to its original wording, prior to August 1, 2018. In early 2024, the government commissioned an investigation to map out the needed regulatory changes to enable and clarify uranium extraction, with the assignment to be reported no later than May 15, 2024. We will be following closely…