A more detailed look at one of Europe’s historically most important mine ⛏️

After an initial summary of the Nordic copper industry in my previous article, I wanted to take a closer look at some of the region’s most important deposits. We’ll begin with the historically important Falun deposit, which played a crucial role in Sweden’s rise to great power status in the 16th & 17th centuries.

Located some 200km NW of Stockholm, the origins of the Falun mine likely date back more than a millennia, with the closure of the mine some 35 years ago ending one of the longest, continuously operating mining operations in the world.

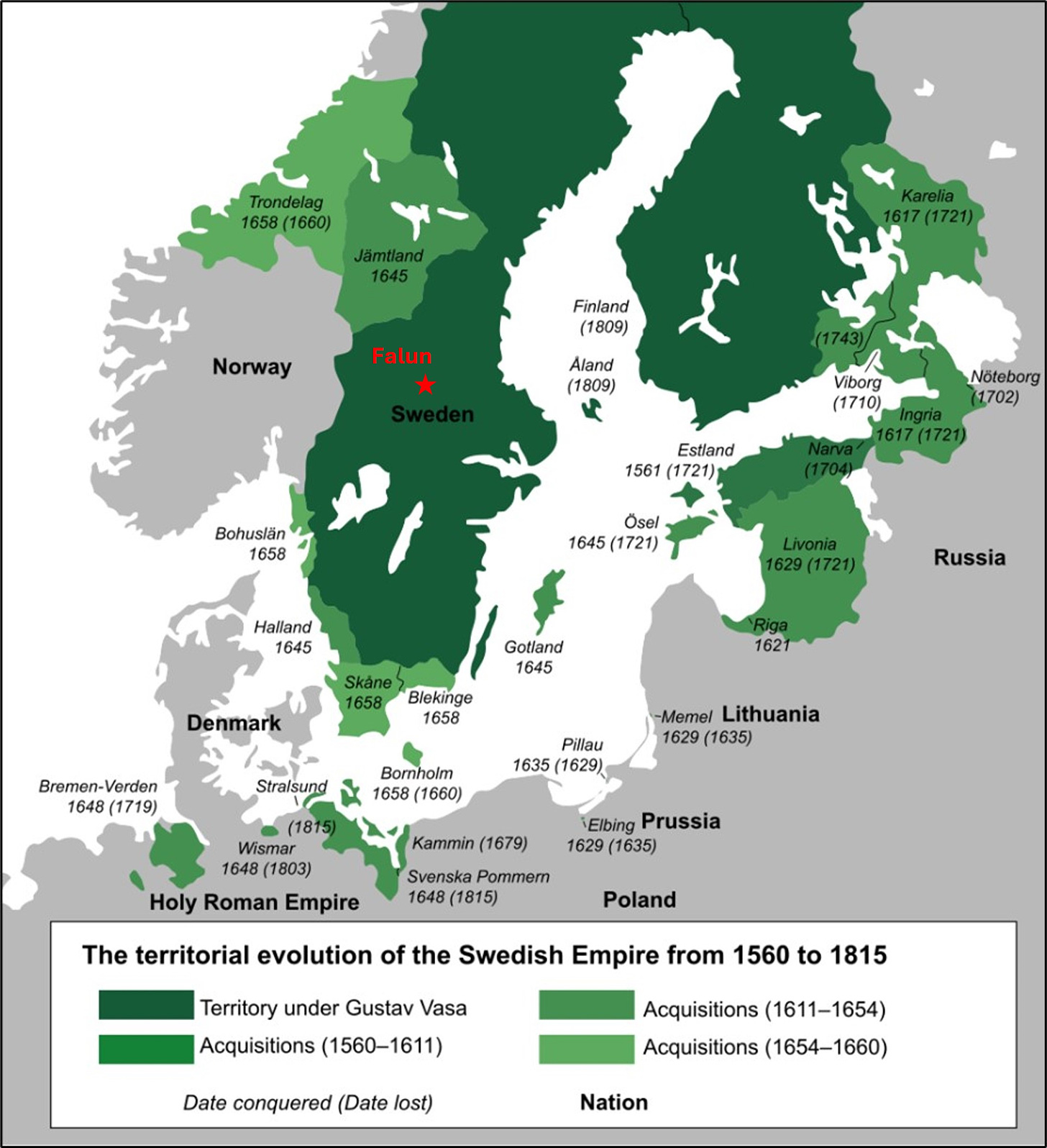

Besides being the birthplace of one of the world’s oldest companies, Stora Enso, the mine’s heyday coincides remarkably well with a time when Northern Europe was dominated by the Swedish Empire. Yes, you heard that right, the pacified Swedes once used their advanced military in an attempt to transform the Baltic Sea into a Swedish lake..

The rise of Falun and the Swedish Empire 📈

After gaining independence from the Kalmar Union and freeing itself from Danish rule at the beginning of the 16th century, the reign of Gustav Vasa resulted in several important reforms and regulations that laid the foundations for Swedish expansion during the coming decades.

In addition to the military and state apparatus, his reforms also modernized the Swedish mining industry, by ways of improved organization, a clear tax system and access to the latest technologies. With dwindling supply from the continents traditional copper mines in modern day Slovakia, it is likely that the king saw an opportunity for his country to capture a larger market share in the international copper trade.

Based on a combination of these reforms, rising copper prices, and the discovery of the richest parts of the deposit, the 1570s heralded Falun’s golden age that lasted for more than a century.

At its peak, in 1650, the mine is said to have produced around 3,000 tons of refined copper, amounting to more than two-thirds of the world’s production.

Not surprisingly, the copper exports from Falun made up a major part of the crown’s income during those years, thereby helping fund the country’s “stormaktstid” from Gustav Adolphus’s successful campaigns during the Thirty Years’ War to the death of Carolus Rex in 1718. As a result, copper from Falun can today be found in many of Europe’s cathedrals and royal courts, with probably the best-known example being the roof of the Sun King’s Château de Versailles.

In addition to the financial benefits from the exports, copper from Falun also contributed to a newly developing, advanced arms industry that gave the Swedes an important edge on the battlefield. (still exists today…🤫)

…and downfall 📉

Following the depletion of the richest parts of the deposit and a major collapse during Midsummer in 1687, the output of the mine declined. Fortunately, as the summer solstice is the most important holiday in the Nordics and the workers were enjoying one of their rare days off, no one got smashed. At least, not from the collapsing pit…

Somewhat foreshadowing the ultimate demise of the Swedish empire, the mine never regained its previous importance to the realm in the pre-industrial age. Copper slowly but surely ceded its spot as the Nordic Kingdom’s most important export commodity to iron ore.

Although the Swedish Empire and its expansionist ambitions ceased with the death of King Carl in 1718, the mine in Falun continued to operate for centuries more, before finally closing its doors in 1992.

If the historic numbers are to be believed, the mine is estimated to have produced more than 1 million tons of copper, together with an exceptional number of “by-products” (28Mt @ 4% Cu, 4g/t Au, 5% Zn, 2% Pb and 35g/t Ag) during its lifetime.

Some more details on the deposits geology 🛠️

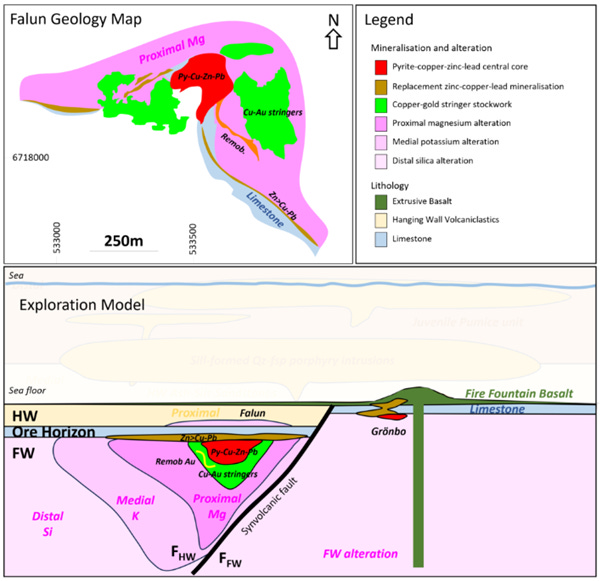

In geological terms, the deposit sits within an almost 2-billion-year-old volcanic inlier dominated by rhyolitic volcaniclastic rocks. The mineralization is hosted by locally reworked rhyolitic tuffs and an overlying, several-meter-thick dolomite horizon which likely acted as a chemical and physical trap. The ore itself appears to be mostly of replacement style and consists of massive to semi-massive sulfides. While modern mining focused on the massive parts of the deposit, the old timers also targeted Cu-Au mineralization, which is inferred to represent the footwall copper stringer system. Interestingly, this stringer system is overprinted by auriferous quartz veins that upgraded the original mineralization, resulting in locally bonanza gold grades of up to 887g/t Au over 0.75m.

Based on the stark contrast between a strongly altered footwall and a generally fresh hanging wall, together with the occurrence of a well-developed stringer system, the deposit is probably best classified as a classical VMS (Volcanogenic Massive Sulifde).

As VMS deposits usually occur in clusters, but only one significant ore body has been found to date, it is easy to understand why the Falun mine and the surrounding volcanic inlier continue to attract explorers. Today, the deposit and the most prospective part of the volcanic inlier are controlled by Australian-Swedish junior explorer Alicanto Minerals (ASX:AQI), who, in addition to the classical exploration methods, strongly relies on a volcanology-based approach to vector towards additional lenses and new deposits.

For the next article in the copper series I am planning a small trip to a prospect I wanted to visit since a while. So, if you haven’t already, make sure to subscribe.✍️

/Nico